The SaaS Fundraising Death Zone – StartupSmart

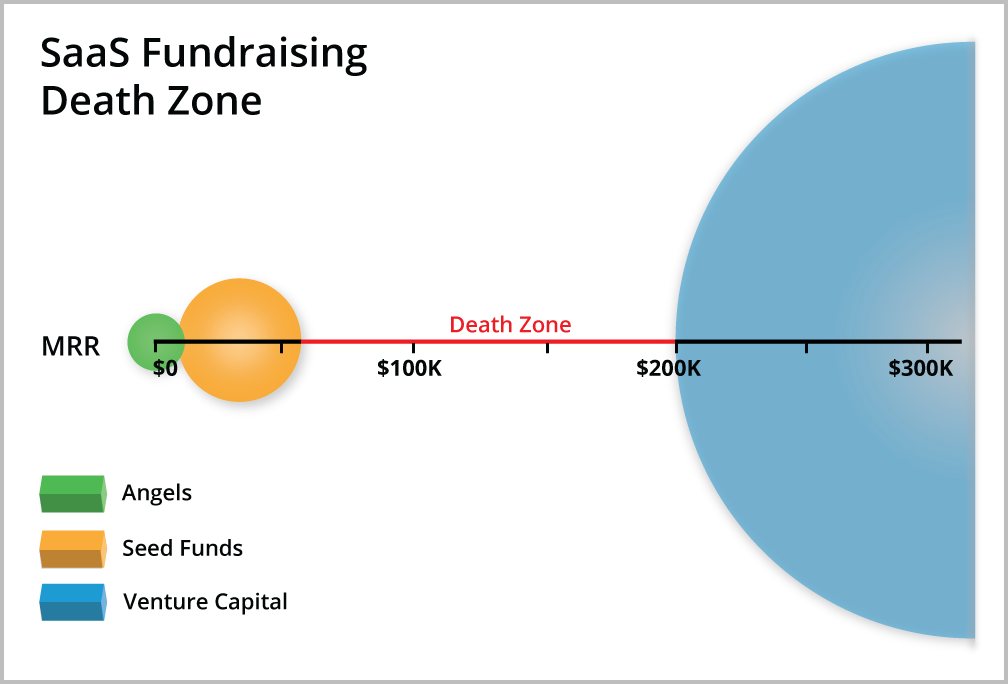

TL;DR: the ecosystem of early-stage investors (angels, seed and VC) has a structure and set of incentives that creates ideal (or even necessary) points in a SaaS startups life for raising capital. Unfortunately, changes in the ecosystem have created what I call a “Death Zone” between Seed and VC tiers of investors which can seriously affect the ability of a SaaS startup to raise the capital they need to grow, and in some cases, survive. For most SaaS startups, the death zone occurs where they are doing between $50K and $200K in MRR: the startup is too big to raise from Seed funds, but too small to raise from VCs, and because it is counter-intuitive, it is a major risk to SaaS entrepreneurs running successful, growing startups.

Building a SaaS company is hard but rewarding. After bootstrapping AffinityLive for its first few years (very very difficult), I decided that the time was right for us to engage with investors and raise capital to accelerate our growth further. Fundraising is always hard work, but I didn’t realize until I was well into the process that I’d made the mistake of trying to fundraise at a time in the business’ life that I’ve since come to call the SaaS Fundraising Death Zone.

This post is an attempt to help other SaaS founders out there not repeat my mistakes, because while our outcome has actually been really awesome, the probabilities of success were much lower and the effort required to get a great outcome was a lot higher than it would have been if I’d known this information a couple of years ago. I hope this post is helpful, and feel free to share it with other founders you think could benefit from it (Twitter, Facebook, mailing lists, etc).

Early Stage Investor Types

Before explaining the Death Zone, it makes sense to summarize the different types of early stage investor active in the ecosystem. This is just my experience and perception, but since these observations underpin my lessons learned, it makes sense to spell them out here.

Angels

Angel investors are those early stage folks who mostly write $25K-$150K checks out of their personal funds to back a company early. They’re usually people who’ve had a good exit from the industry or have risen in it enough to qualify as an Accredited Investor – they’ve got their own nose for picking winners and often their main payoff is the emotional satisfaction from investing (paying it forward, giving back, being able to share the excitement of the early stage journey from a front row seat) – early stage companies are so risky most Angels would get better financial returns from playing table games in Vegas. As a very small time angel investor myself (through Startmate) I treat every check I write as a donation in the balance-sheet of my mind.

Seed Funds

Seed Funds are those early stage investors who mostly write $750K-$1MM checks for companies that have shown some promise and have achieved more traction or have a more compelling team/vision/opportunity that allows them to bypass (or combine) angel investors. They tend to raise smaller funds (anywhere from $10MM around $100MM, but they’re raising more too) to invest in startups, and most of the time they’re backing companies based on their belief of their ability to get to a Series A.

Most of the time these Seed Funds are newer and as they prove out their track record they raise larger and larger funds which let them write bigger checks and graduate into “VC Funds” land – you could argue that some of the names below are already there.

Prominent examples of these types of funds are SoftTech VC (2015 fund was $85MM), XSeed (2012 fund was $60MM), 500 Startups ($100MM in 2013), Illuminate Ventures and Costanoa Ventures ($135MM in 2015).

VC Funds

VC Funds are the folks with the big firepower – they raise many hundreds of millions, sometimes into the billions from their investors to then put to work investing in startups. Names like Kleiner Perkins ($525MM fund in 2015), Sequoia ($700MM in 2010), Andreessen Horowitz ($1.5B in 2014), Accel ($475M just for early stage in 2014), Greylock ($1B in 2014) and Benchmark ($425MM in 2013) are prominent in this category.

These funds invest in companies they think can be IPOs and billion dollar exits, and while some of them do seed investing (often writing $500K checks alongside others) they really get into the game and place their bets at the Series A stage (all the partners I’ve spoken to at these firms who do seed investing just to get the inside run on the Series A) and then follow on (or join in someone else’s party) in Series B and later stages.

OK, now we’ve gotten that out of the way, let’s look more clo

SaaS Valuations

Valuations are a funny thing – the true answer is that a company is worth what someone will pay for it. In early stage SaaS, however, when there’s a lot of uncertainty but there’s some proof points, a good rule of thumb is to consider the valuation of the business as being 10x annual recurring revenue (ARR). Applying this rule of thumb, if you’re doing $50K in monthly recurring revenues, your current rule of thumb valuation $6MM.

Now, if your SaaS business is growing fast (more than tripling or doing 200% a year in revenue growth), you can expect to see this multiple move up to 15x-20x. If you’ve tapped into something super lucrative and frictionless (Zenefits, Slack) you’ll see these multiples go a lot higher because investors are happy to overpay now if they’re very confident you’ll be worth that higher price very soon. While we all like to obsess about outliers (and aspire to be one), it makes sense to look at the more general case of a successful SaaS business that has solved a real problem and is doubling revenues year on year.

The reason for bringing up valuations is that the process of raising equity funding involves “selling” some of the company to new investors (although mostly by issuing new stock, so the company gets the money, not existing shareholders). You might think that raising $2MM for a company that is valued at $6MM is much the same as raising $2MM for a company valued at $40MM – you’re just selling a smaller percentage of equity – but you’d be wrong because investors have different needs.

Incentives for Early Stage Investors

For everyone in the early stage except the Angels (and sometimes also them), there’s a very strong incentive for an investor to buy 15%-20% of startup when they invest in a funding round. In fact, from talking to dozens of investors and many more entrepreneurs about it, the percentage is actually the fixed aspect in the investing formula – increasing the check size just increases the valuation, but the percentage is the piece that is fixed in place.

The reason for this is that investors know many of their investments are going to be duds and return nothing at all, some will return nicely, and occasionally they’ll get a massive home run which makes almost of the money in the fund. It is known as a power-law, and Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen do a great job explaining it. The consequence of this arrangement is that investors want to make sure they have a meaningful piece of each company they invest in (they believe each one will be the home run when they invest, otherwise they’d pass) so the returns are great if they’re right. They’re also conscious of their own time in selecting and then working with/helping a startup they invest in – if they only have 5% of a company, they’ll be a lot less excited to work alongside those founders than they would be for a company they own 25% of.

So, if the percentage is the thing that investors doggedly stick to and the valuation rises and falls with the check size (amount they invest in that round), why is there a death zone? Well, it turns out that check size is in many ways defined by the size of the fund and funds aren’t nearly as flexible as we’d like.

Fund Size and Check Size

The early stage business model for a fund (Seed or VC) is pretty similar – the fund raises money from Limited Partners (LPs) who are looking for a return on their investment – usually they’re wealthy family offices, college endowments, pension funds, etc. When the LP invests in a fund, they’re handing over their money for a period of 10 years (roughly). The fund then invests that money in startups, front-loaded often into the first 3 years, and then “follows on” with the successful businesses to keep their percentage as high as possible through future rounds of investment.

Seed Fund Check Sizes

To use a specific example, let’s look at a Seed Fund which has raised $60MM (to keep the math easy). With a $60MM fund, the investor is basically saying they’re going to invest $20MM a year for the first 3 years (leaving the back 7 for the companies to “exit” and return the cash through an IPO or sale). In reality, though, they’re not spending $20MM each year – when they invest they keep funds in reserve for each investment so they can “follow on” in future rounds and maintain their stake. While the ratio of first money to follow on reserve for each fund varies a bit, from the early stage funds I’ve spoken with the ratio tends to be around 1:2, or one third up front, two thirds for follow on.

This means of the $20MM per year they’re trying to commit for the first three years of the fund, they’re actually writing $7MM in new money checks, and keeping $13MM to follow-on with the future rounds of funding for the successful companies.

Dividing this $7MM through, if they’re doing 8 deals a year (two a quarter is a good rule of thumb), they’re writing an average $875K check, meaning they’re probably tapped out writing checks much past $1MM for their first money in.

VC Fund Check Sizes

Now let’s look at a VC fund like Greylock Partners. They have the same fund lifespan (10 years), but they’re working with $1B (which is up from the $500MM fund they raised in 2005). This comes out to $333MM a year in the first three years of the fund’s life. These bigger funds aren’t putting all of their fire-power in at the early stage, but given the big multiple returns happen there it is probably fair to assume they’re putting half of their fund into early stage investments ($166MM a year), and using the 1:2 ratio between first round and follow on reserve, this means they’re needing to put to work $55.5MM a year in early stage deals. Assuming the fund is doing 8 of these Series A deals a year, they’re having to write a check of $6.93MM for each of those deals for the numbers to fall out. Looking at actual data, the average Series A round was $6.9MM in 2014, so this isn’t a bad general guess (and anecdotally prestigious firms like Greylock don’t fit into the average so the thought of them writing $7MM+ checks as part of above-average Series A deals makes a lot of sense).

You might be thinking, “well, these guys have a lot more money to play with – so why wouldn’t they do a deal where they buy 20% of my awesome startup for $3MM, spending half the money they do on average? That makes us a bargain!” In practice, this doesn’t happen much because the VCs know they have limited bandwidth and they really need to shovel this money from their LPs into startups to make it all work. If they were to invest an average of $3MM in a deal, they’d have to work twice as hard for their management fees – and they didn’t buy that place in Jackson Hole to leave it empty for months at a time.

They could of course write the same big check with your startup at a lower valuation, but then they’d be taking 40% of the company – crowding out the other shareholders, especially the ones who need to work their butts off for the next 5-7 years to get the company to an exit, which is why only predatory investors do this in the early stage.

Now, while it isn’t necessary for a Seed or a VC firm to be a slave to these averages (they might keep less in reserve to follow on because they’re on a tear and know they’ll be able to follow on with the next fund they’re out spruiking now), and there are certainly many exceptions that prove the rule, the size of the fund certainly does define the parameters of the partners when they’re writing checks – Jeff at SoftTech isn’t likely to write a $10MM check to a startup he really likes because that means sinking almost 12% of the current fund in one bet.

Looking at the fund size, check size, incentives and SaaS valuations together exposes the SaaS Fundraising Death Zone.

The Death Zone

When a SaaS startup is very early (little product, no revenue, showing promise), Angels will often invest on a convertible note, essentially an IOU which the company converts into investor shares at a future financing round. Commonly these rounds are in the neighborhood of $500K from 10-20 individual investors on a note often capped at $4MM (which gives an implied valuation of $4MM for the startup and means the angels collectively will have 12.5% of the company when they do a priced round).

Once the company has some traction and proof points, they’ll want to go beyond the prototype engineering team and invest money into acquiring customers. To do this, they’ll often raise a round from a Seed fund with more firepower than Angels can provide. Given Seed funds will want to write around a $1MM check, and because they want to target the 15%-20% ownership stake, the pre-money valuation at the Seed stage will likely be not much more than $6MM – which using the 10x ARR principle means the startup will be doing $50K in MRR if they’re doing well, or a lower amount of recurring revenue is their growth rate is awesome.

The company then puts the funds from their Seed round to work and builds the revenues up to $200K in MRR. Using our 10x rule of thumb, this gives them a pre-money valuation of $24MM, and a check of $6MM will give the investor at the Series-A a 20% stake of the business (post money). They then keep on building, raising money on the way as they need, and then either get acquired, go public, or completely screw it up and die.

The problem is the gap between $50K in MRR (where Seed funds top out) and $200K in MRR (where the VCs start to do their Series-A deals) – and it is a gap I’m calling the Fundraising Death Zone.

Entrepreneurs who try and raise between these two points are at a significant disadvantage – they’ve basically got four difficult options.

- You can accept the rules of the game and raise $1MM from a Seed fund at a lower valuation than they’re worth (the $6MM cap which still gives the Seed fund the % ownership they want). A lower value means more dilution (you can only sell equity once), but the Seed fund really can’t write a bigger check and if you need capital, you might have to take what you can get.

- You can convince the Seed fund investor to lower their percentage requirements. This isn’t easy at all and involves great salesmanship by the entrepreneur to convince the Seed fund investor that having a smaller percentage of a massive winner for a check size they can write is better than having 0% and missing out on the winner entirely because of their fixation on maintaining a certain percentage.

- You can convince the VC investor to give you a valuation your business don’t deserve (now) and raise a big round, which is the more common scenario if you’ve got something great going for you (reputation, team, media buzz, VCs or their portfolio companies use the product themselves, etc). This can however be a poison pill in the medium term because you need to earn the valuation you’ve been prematurely given, and then earn a future higher valuation to ensure you don’t end up with a down-round.

- You can convince the VC to write a smaller check, increasing their relative workload. This also requires a lot of salesmanship and the only way to really make this happen is to make it clear you’re coming back for a bigger check in the near future at terms that will be favorable to them (the balance of a check size they want at a not-crazy valuation).

Now, this doesn’t mean fundraising in the Death Zone is impossible – it just gets a lot harder. Professional investors are spoiled for choice in the early stage with lots of companies crossing their path, and when something doesn’t fit their pattern of valuation, stage and check size, it is a lot easier for them to pass and harder for you to build competition in the deal.

The real problem with the Death Zone is that it seems counter-intuitive – surely a company that is doing $120K in MRR can raise money a lot more easily than a company doing $50K in MRR? It is more than twice as successful revenue-wise, has been de-risked more and it is a lot harder to fake $120K in MRR than it is to get to $50K with some clever but unsustainable growth hacking. Investors must be a lot more into a company doing $120K than one doing $50K!?!? While it doesn’t make sense for entrepreneurs, the needs of early stage investors and the limits on the check sizes they will write means often this isn’t the case at all.

This counter-intuitive nature is the big risk for SaaS entrepreneurs. It makes logical sense to think “hey, we’ll hold off from fundraising now until our numbers are better, we’ll get a better valuation from better investors”. But the reality is, if you blow past $50K in MRR, you’re going to want to make sure you’ve got the internal resources to more than 4x the size of the company or else you’re going to face a shitty or much more difficult path to successful fundraising – especially if you need to raise capital in the Death Zone.

I hope this has been helpful – if you’ve had different experiences or have a different perspective, please share them in the comments below!

This article was originally published on geoffmcqueen.com